Overview

Welcome to Unit 1 of Learning with Technology! This course will introduce you to some ideas related to living, learning, and working in our digitally saturated society. It is our intent to equip you with an emerging set of skills and literacies related to digital tools for learning. Within your academic pursuits, you will encounter a vast amount of information—integrating digital tools into your learning journey, though challenging, is essential for harnessing the ample learning possibilities offered by your chosen discipline. This course will give you a head start on using digital tools to build a workflow, enabling you to stay organized and to make your learning process visible to both you and your instructors. We will also lead you through readings and discussions on topics such as digital identity, privacy, security, and ethical ways of sharing newfound knowledge.

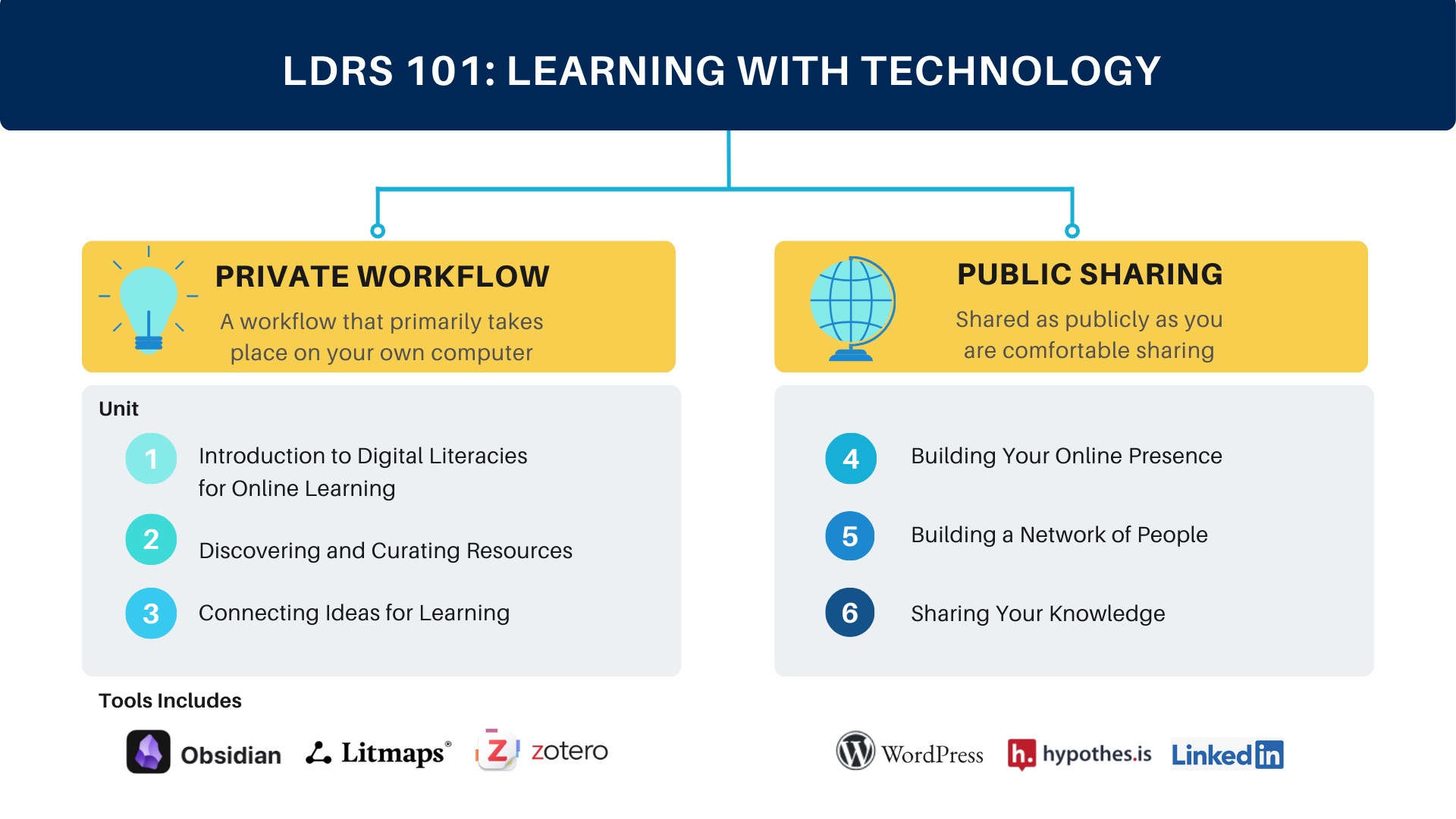

There will be two primary branches of the course, each focusing on specific tools that we will introduce to you. The first branch will be a workflow that is private to you because it takes place primarily on your own computer, and the second branch is shared as publicly as you are comfortable sharing. You will have control over how public your work is, but we will think about the importance of sharing knowledge and how to do that easily and in ways that preserve your “ownership” over your work.

Please note that we will invite you to sign up for some web-based tools (LitMaps, Zotero) and we hope you will feel comfortable doing that. We have vetted and personally use the tools we recommend here. If you are uncomfortable signing up, please let your facilitator or instructor know and we will be happy to talk about options, including signing up anonymously. You will not have to pay for any of the tools that we suggest.

See the following graphic that gives an overview of the structure of the course, including important tools we will explore.

In this first unit, there will be both theoretical and practical work for you to do. We start with some basic instructions and advice on technology and learning online. Then, in order to build a theoretical understanding of digital tools for learning we will explore the idea of “the digital” in the context of contemporary society. At the same time, there are some important practicalities to manage in order to get set up for the course, so we will lead you through installing some apps on your computer that you will use extensively in this course, and which hopefully will become the backbone of your digital workflow throughout your time in higher education and beyond.

Topics

This unit is divided into the following topics:

- Learning Online

- Understanding the Digital

- Digital Literacies

- Digital Privacy and Safety

Unit Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this unit, you will be able to:

- Describe your engagement with digital technology

- Apply digital tools to support learning in an academic environment

- Explain what digital literacy means to you

- Examine privacy concerns related to various platforms and tools

- Describe how to protect yourself and others in the digital environment

- Identify goals for developing digital literacies

Learning Activities

Here is a checklist of learning activities you will benefit from in completing this unit. You may find it helpful in planning your work.

Assessment

See the Assessment section in Moodle for assignment details.

Resources

- All resources will be provided online in the unit.

1.0.1 Activity: Setting Your Learning Goals

1.1 Learning Online

In face-to-face teaching environments the requirement to physically attend class, coupled with community accountability, makes a learner’s individual learning skills less relevant for academic success. However, when learning online there is less instructor oversight, motivation, and accountability, requiring the student to have the skills required to learn effectively. While a face-to-face instructor might notice that their student is absent, confused, or falling behind, and will check in on their well-being and offer support for their success, an online instructor often has less opportunity to do this. The learner is therefore required to have strong learning skills, recognize their responsibility as a self-directed learner, and practice these skills accordingly.

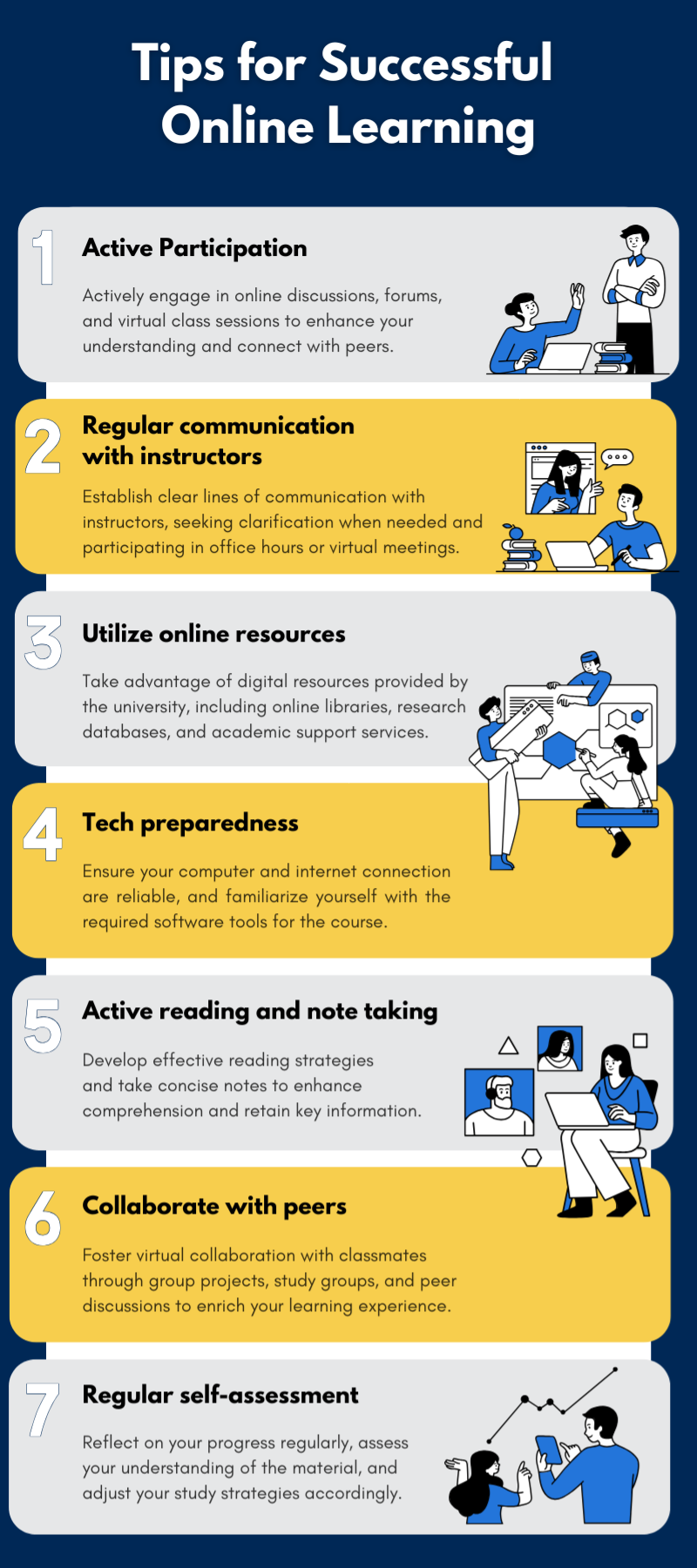

Online learning requires additional skills differing from face-to-face learning, and since online learning is often self-paced, an absence of these skills will make a student’s learning experience difficult. According to Crozier and Lake (2020) these skills include:

- Time management (i.e., effectively managing deadlines, schedules)

- Organization (i.e., creating a dedicated study space, ability to easily access material)

- Self-motivation (i.e., scheduling set times for coursework, peer study accountability)

- Self-regulation (i.e., strategies can include breaks, physical activity, meditation)

- Strong written and oral communication (i.e. technical writing skills, ability to communicate with others and ask for assistance if needed.)

Here are a couple more ways you can hone your online learning skills:

Remember, flexibility and adaptability are key in the online learning environment. Tailor these tips to your individual needs and the specific requirements of your courses. Note also that you will have opportunities to practice these skills throughout the course.

1.1.1 Activity: Learning Online Effectively

1.1.2 Activity: Engaging in Online Discussions

Discussion Guidelines for LDRS 101

In this course, we will ask you to discuss ideas with your peers via Learning Community, WordPress, and other social media platforms. These discussions are ungraded, meaning, your instructor will not give you marks per discussion. However, they are an important part of this course and you will not be able to complete your assignments without discussing with your peers. Consider for example, two course learning outcomes that relate to online discussions:

- Develop personal and professional learning networks to discover and share knowledge, collaborate with others, and become engaged digital global citizens

- Create inclusive digital communities which embody a sense of belonging, connection, and Christian hospitality

Your discussion posts may be used as learning artifacts to demonstrate your understanding of the course learning outcomes (see Assignment details in Moodle).

In LDRS 101, you should write your posts in a way that shows you are communicating in an academic setting. While you don’t need to adhere to all of the conventions of APA formatting, you should practice the principles of proper citation. For example, to cite an idea from the article in the previous activity, it would look like the following (Galikyan & Admiraal, 2019), and the bottom of the post would include a “References” heading, followed by the full reference (this part may be considered optional since we have included a link to the article in the in-text citation, but it is nice to have). Please consult the APA Style website for details.

It is highly recommended that you begin using a reference manager—we recommend Zotero as it is a free and open source app with all you will ever need to cite properly in any style. We will lead you through some specifics of using Zotero in the next unit of LDRS 101, but you can download Zotero for free.

In short, similar to a live classroom discussion you need to be polite and professional, and you need to provide evidence for your views, but, as in a normal conversation, you won’t have all of the formalities of academic writing. In LDRS 101, you should consider your forum posts as a time to practice and test your ideas. The stakes are very low, so it is fine to make mistakes.

In online discussion forums, learners are encouraged to respond substantively. What does this mean?

Work through the following slideshow for more information.

For more on substantive participation, read Writing a Substantive Discussion Post for an Online Class Forum (2016).

1.1.3 Activity: Join the TWU Learning Community!

The Learning Community is a critical component of online courses at TWU because it provides a single space for you to connect with your facilitators, instructors, and, most importantly, other learners completing this and other online courses at TWU. Your privacy is protected as you will be signing in through TWU systems.

You will notice that you see categories for other courses when you sign in. This is intentional because we want you to be able to connect with a wide variety of learners in a wide variety of courses. This structure also allows you to discuss topics that span multiple courses, such as ‘#leadership’. You are welcome to explore other course categories and to consider Learning Community as your digital campus.

1.2 Understanding the Digital

Our next topic is an introduction to the idea of “the digital.” You may recognize that digital tools are deeply embedded in modern society. It is not uncommon for people of all ages to interact with apps and tools that claim to connect people in conversations or networks, or to perform complex tasks for work, or to control various systems in our vehicles. Digital technology is really everywhere we look. Thinking about these tools is one way to conceptualize how we interact with digital tools but we can also recognize that our social practices and norms have been impacted by digital tools. An example of this, at least in North America, is that the names of companies have become verbs. If people want to learn something about a topic, they Google it.

Mobile phones are often essential tools for communication, social media, internet browsing, messaging, entertainment, photography, navigation, online shopping, mobile banking, productivity, two-factor authentication for some websites, and health and fitness management. In some cases, such as in social media, it is almost impossible to participate in public discourse without access to technology.

Modern universities are also deeply impacted by the digital. Every system involved in higher education has been digitized in some manner, including recruitment, accounting, and fundraising. At TWU, here are some digital systems you will likely encounter:

- Courses are designed and often delivered digitally.

- Course logistics (discussion forums, assignment submissions, quizzes, gradebooks) happen in large digital tools called learning management systems (LMS) or virtual learning environments (VLE) such as Moodle.

- Assignments must often be created digitally (using word processors, presentation software, video editors, website builders).

- Research data is gathered, stored, analyzed, and shared digitally.

There are many other processes and procedures that rely on the digital in higher education, but the important thing for you to realize is that there are many tools that you will be required to learn and use. Some are obvious, such as word processors, presentation software, email, the library website, and the LMS, but others are less obvious and won’t necessarily be taught specifically, other than in this course.

Some of the digital tools we will introduce to you will help you build a workflow for you to manage the huge amount of information and resources that you will have to sort through to complete many of your assignments. You will learn to use AI to find relevant resources on whatever your topic might be. As you may know from searching Google, a simple search of the web can turn up thousands or millions of hits, but there are tools that can help you highlight the most relevant resources in just a few clicks.

Once you find resources, we will show you tools that will allow you to track all your references, create citations in your writing quickly and easily, and then create a perfectly formatted reference list. Do not waste your time creating your own bibliographies! This one tool will save you days and likely weeks of work during your degree (quite literally).

We will show you another tool that will allow you to make connections between ideas and notes so that you build a network of connected ideas. Curating this network of ideas is possibly one of the most useful things you can do. You will end up with a searchable network of everything you’ve learned and be able to visualize it at the click of a button.

Additionally, we’ll guide you through thinking about your digital presence. You’ll learn to make wise decisions about how to present yourself online, what to share, and how to share it. We will also help you make connections on the web that could become a key resource for your learning and working in your career.

As you watch the upcoming video, think about how these digital tools fit into your own learning and professional journey. Which tools resonate most with your goals and aspirations? Consider how you can tailor your focus to build a digital toolkit that not only supports your academic success but also aligns with your long-term professional trajectory.

1.2.1 Activity: Reflection on Self-Directed Learning

1.3 Digital Literacies

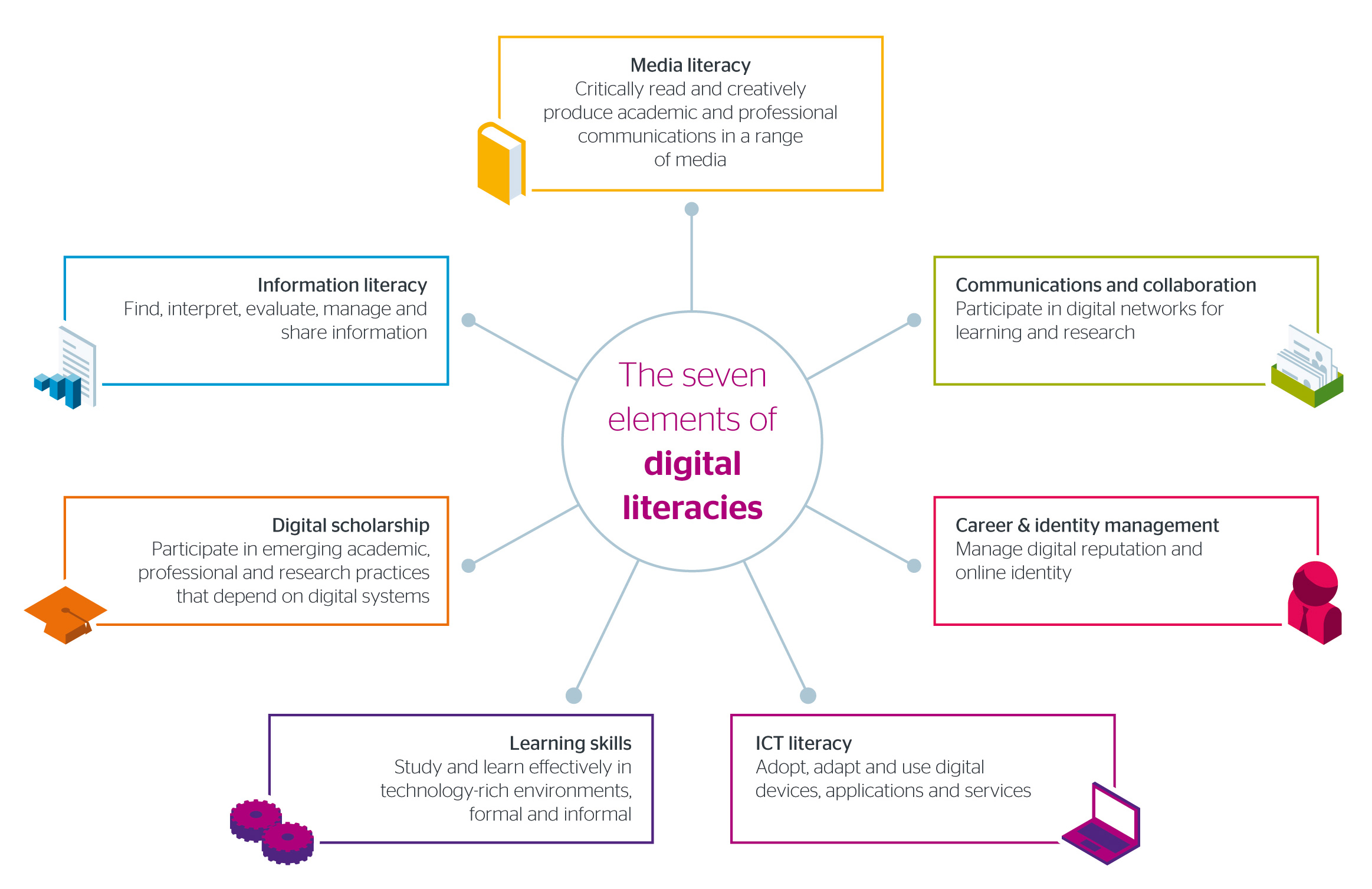

Digital literacy is a person’s knowledge, skills, and abilities for using digital tools ethically, effectively, and within a variety of contexts in order to access, interpret, and evaluate information, as well as to create, construct new knowledge, and communicate with others. (British Columbia Ministry of Education, n.d., p. 23)

Literacy, as we commonly understand it, is the ability to understand the meaning of texts. It is more than just being able to read. In the same way, digital literacy is the ability to make meaning using digital tools. It is more than simply being able to post to Instagram or TikTok, or whatever app you might use. As the definition above indicates, digital literacy involves using tools ethically, to access, interpret, evaluate, create, construct, and communicate information and knowledge.

“In today’s world, being literate requires much, much more than the traditional literacy of yesterday.” (Alber, 2013)

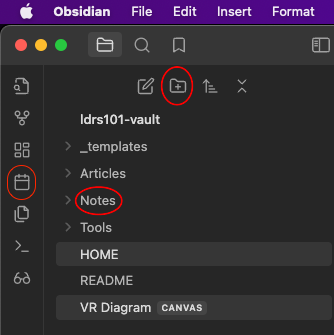

What digital tools do you use to help you make meaning? What is your “go-to” app for note taking, organizing files, tracking references, and connecting ideas? One valuable tool we are going to show you is called Obsidian, a free note taking and mind mapping app. Before you go through the instructions in the activity below, watch the video This is Obsidian. (2021).

1.3.1 Activity: Getting Started With Obsidian

Obsidian is the first tool that we will ask you to use that requires you to download a program and install it on your computer. As you work through the instructions for installing Obsidian and getting started with the starter vault, keep in mind that you will almost certainly encounter things that don’t work in the way that you expect them to, or that don’t seem to match the instructions. That is ok, and it is important for you to not get discouraged. We know that you likely don’t know how to do some of these things, and that is the whole point of you taking a course…to learn things! The almost universal feeling when people are learning something new is frustration. Do not feel bad about feeling frustrated. Instead, go back and check the instructions to see if there was something you missed. If that does not reveal anything in a couple tries, please reach out in the Learning Community! We will direct you to resources and conversations where others who have gone before you have worked through all the same issues.

One of the most important things we can do in learning is to get things wrong, then reach out for help.

Obsidian will become a backbone of this course as we will use it to learn how the web works and give you a workflow that will help you stay organized. One of the advantages of Obsidian is that everything you do in the app happens on your own computer, rather than the cloud, which is just another way of saying someone else’s computer. However, the drawback to that is that you need to ensure that you have a backup of your vaults in a secure location, either one of the sync services mentioned in Step 3, above, or another backup system. Please check the Learning Community or talk to your instructor or facilitator for help with this.

1.3.2 Activity: Reflection on the Evolution of Digital Technologies

Digital Literacies and Skills

Digital literacies for academic learning involves more than Facebook, Snapchat, or BlueSky and the associated technical skills in using these technologies.

As you explore the concept, you will find online resources which confuse digital skills with digital literacies. The activities which follow aim to provide an initial introduction to the wide range of digital literacies associated with academic learning. We will explore the concept of digital literacies in greater depth as we progress with the course. When exploring these online resources we encourage you to differentiate between skills and literacies, and to develop a critical disposition. Digital literacies involve issues, norms, and habits of mind surrounding technologies used for a particular purpose. However, these literacies are closely related to technical proficiency in using a range of digital applications.

In the next activity, you will start to unpack these terms and prepare your own initial definition of digital literacy.

1.3.3 Activity: Defining Digital Literacy

1.3.4 Activity: Why Digital Literacy Matters

1.3.5 Activity: Am I Digitally Literate?

Visitors and Residents

One way to start thinking about digital literacy is to create a map of the apps and tools that you use, how you use them, and what traces of your presence you leave behind on the web. We call this a Visitors and Residents Diagram. To complete this activity, we’ll first discuss some key concepts.

Have you encountered the terms “digital natives” and “digital immigrants?” What are your initial thoughts on their definitions?

The essential argument is that certain generations have changed, in that they have an innate ability to use and learn technology because they have grown up using technology, and those generations whose formative years pre-date the advent of the internet are forever at a disadvantage compared to kids. You can read a bit more about the idea on Wikipedia: Digital Native(2025), linked below. There is also a link in that article to Prensky’s original article.

Aside from the problematic framing of learners as kids, there are some distinct challenges with the idea of digital literacy being a fixed trait rather than a matter of comfort, familiarity, and a skill that can be practiced and learned. It is no secret that young people are comfortable using social media apps such as TikTok, Instagram, SnapChat, Weibo, WeChat, and the like, but this doesn’t imply a superior aptitude for learning technology compared to older generations, or an inherent proficiency in doing so. For example, are most first-year university students proficient in using a spreadsheet to create a budget? If they have created a budget, it’s more likely they use an app than a spreadsheet.

We’d like to introduce you to a different way to conceptualize your relationship with digital media, and that is that you may be a visitor in some web spaces and a resident in others. Places on the web where you might be a visitor are those places where you quite literally visit, but importantly, don’t leave a public trace of your time there. You don’t spend any time interacting with people, but rather, you take a rather utilitarian approach by visiting a site, doing a thing, and leaving.

Alternately, there are places and spaces on the web where you reside as a persona, where you interact, socialize, and leave traces of yourself online. For some, that may be Facebook or Instagram, where you keep in touch with friends and family, or X (formerly Twitter), or maybe it’s a blog, or social site. The important distinction is that these are places where you connect with other people, where you are socially present.

At the same time, if we can imagine the visitor \(\leftrightarrow\) resident continuum on a horizontal axis, there is also a personal \(\updownarrow\) professional (or educational) continuum on a vertical axis, leading to four quadrants where you might situate your technology use.

1.3.6 Activity: Where Am I Online?

Now to the task of creating your own Visitors and Residents Diagram.

See the diagram below … keep in mind that this diagram represents a set of tools that its creator has been using for a decade or more, and that they have invested their career in educational technology. There is a lot here; yours might look significantly different with only a few tools here and there. Or perhaps your diagram has a plethora of tools you use regularly. The key idea of visitors and residents is for you to think about which technologies you use as a resident, and then to think about which tools you may have tried or are interested in pursuing. From there, we can begin to plan for tools we can use that afford us the opportunity to reside there.

It is certainly notable that this diagram’s creator is very much a visitor in Moodle! This does not mean that they don’t spend much time there, they spend a significant portion of every day working in Moodle, rather, the work that they do there leaves very little trace of their personality. You will (hopefully) see Moodle as much more of a place where you reside. But this foregrounds the question of whether Moodle is actually designed to promote residencies. Certainly the forums allow for users to project their persona into the system, as do a few of the other features, but the system itself is very heavily templated. There are profiles that can be edited, but users are limited to one very tiny image, and virtually no opportunity to determine for themselves what they want to share. There is little room for customization, and every time a course ends every single user must recreate their persona in a new course site (or five).

For many university students, a Learning Management System (LMS) like Moodle is a perfectly reasonable place to reside and they feel comfortable accessing course materials, finding their grades, communicating with classmates, and so on. And just like our physical homes, the quality of the community that lives there isn’t determined by the features of the house itself, but by the people who share the space and how they structure their time and interactions.

1.3.7 Activity: Create a Visitor and Resident Diagram

1.4 Digital Privacy and Safety

Now that you have assessed some of your digital skills or literacies, let’s focus our attention on privacy and safety. In this section we summarize important practices as a reminder to remain vigilant in protecting your privacy and security online. If you are unsure about good security practices, there are a wealth of online resources you can (and should) consult.

Privacy

Your privacy is fragile, easy to lose instantaneously, and difficult to retrieve in an environment that requires so much online interaction.

- Identity theft (2025) happens, frequently.

- Never put your social insurance number, your birthday, your mother’s maiden name, or any other personal facts anywhere online. Everyone on the internet will be able to access this information.

- Always assume that anything you write online (including email) can, and probably will, eventually leak. Keep your email address private—to avoid receiving spam. If your email is published in a plain form anywhere online, even if it is part of an archived email list, spammers will “harvest” it for their databases.

- Spam email (at least half of all email being sent) is an unfortunate fact of our modern lives.

- If you must publish your email address online, consider creating a “sacrificial” email address, or one you only use to publish online. You can create an email “alias” which you can set to automatically forward to your primary email, and easily disable if your spam volumes increases. Many email services will automatically generate random email addresses that you can use to hide your true address.

- Another approach is to avoid publishing the email address as something like mailto:myname@somewebdomain.net. Instead, you might use more confusing text, such as myname-at-somewebdomain-net. Some websites support using these types of obfuscation methods, but the spammers who “scrape” email addresses from websites to populate their spam databases use increasingly sophisticated methods to defeat these methods.

- Basically, avoid publishing the email addresses you value online to decrease the amount of spam you receive.

Passwords

What about passwords? Many people have just one, or maybe a few. Given the number of websites and web services which require password-based authentication, this is not good enough to avoid an identity disaster.

The problem with having only a few passwords is that even resource-rich and security-critical organizations have suffered massive leaks. If even one of them suffers a data leak, identity thieves will obtain your password and try to use it on other websites. It is easy for them to do this using computer technologies.

Other ways someone can get your password include:

- Sniffing traffic when you log in to a nonsecure website that uses http:// rather than https:// (the “s” stands for secure because your data transmission’s encrypted). Look for the Lock icon.png in your address bar.

- Sniffing emails—your email, unless encrypted, is not secure. Never send a login and password along with the web address of a service (similarly, don’t send credit card numbers).

- Phishing (2025) attacks—where someone sends you an email that looks like it is from a trusted sender, such as from a friend, your bank, an online store you frequent, or a government agency, and asks you to enter your password to confirm it. No one should ever ask you to enter your password via email.

- Always check the web address (hover over the link) to make sure it corresponds to the right place or call the sender to confirm the request over the phone.

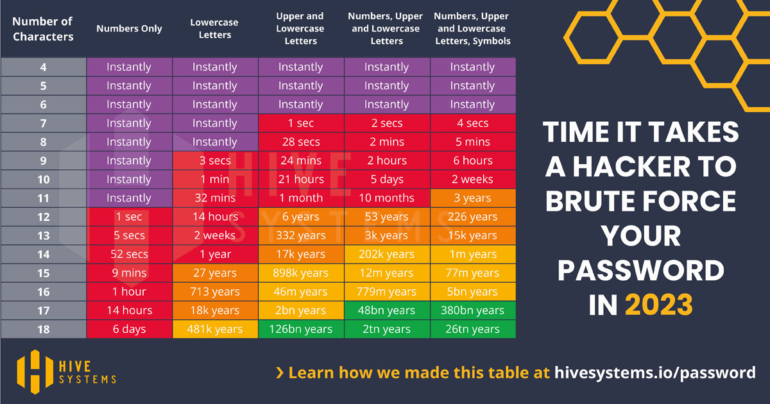

- Brute force—hackers often use computers to guess your password, beginning with a list of common passwords, and try different combinations until they get it right, or until the system locks them out for trying too many times.

- “How secure is my password” sites—you should avoid these sites and never type your password into a website or email response that is not appropriate, especially when you know the sender also knows your email.

- Once your email and any password combination are known, identity thieves will try to use them at various websites, because they know most people only use a few passwords. A thief who discovers a password you created for a website you rarely use will try to compromise the security of a website that is important to you such as your email system, your workplace, social media accounts, or bank account.

Here is a table that shows how quickly passwords can be cracked using brute force methods. Note that the best passwords are both long and include a mix of numbers, lowercase and uppercase letters, and symbols.

Source From “Are Your Passwords in the Green in 2023?,” by C. Nesky, -Neskey (2023), Hive Systems (https://www.hivesystems.com/blog/are-your-passwords-in-the-green-2023). Copyright 2024 Hive Systems. Reprinted with permission.

There are services you can use to check if your email is part of a leaked password data set. So, what can you do to protect yourself?

Password Managers

Get a password manager (2025). They are incredibly helpful and convenient now that many of us use several computers and mobile devices. Password managers help you manage your passwords.

- When you choose a password manager make sure you create one strong password, such as a full sentence with some numbers and special characters. This is all you need to remember—the password manager remembers the others. The ensures you generate a different, fully random password for each website you use that requires a password.

- Good password managers only ever store your details in an encrypted form, where even the company that stores it cannot see your passwords. To access your passwords, you log into the password manager service using your single, strong password (via a secure web link—usually the default, but always check!).

- There are many password manager options. Some widely used proprietary options include Lastpass and 1password. Open source options also exist, such as Bitwarden. Sadly, some of the most popular password managers have suffered from software bugs that have exposed user passwords.

1.4.1 Activity: Get a Password Manager

Good Messaging Hygiene

Always assume that anyone can and will read anything you write in an email. Email is not a secure form of communication. Few people encrypt their email because it is an extra step that even the most technically inclined users are reluctant to take. Both sender and recipient have to be technically proficient.

Text messages and instant messaging programs such as Facebook Messenger are also insecure. Anyone, including government officials and the organization that runs the service, such as Facebook employees, can read it.

Secure Your Own Privacy

Never send any sensitive data such as your social insurance number, credit card number, password, or other personal information via email or text. Call the person to provide this information over the phone.

You can use a secure, encrypted text message service such as Signal if necessary. It is available at no cost, works on most platforms, and encrypts text messages on your phone. If you text someone else with Signal installed, the entire transaction is encrypted.

Secure the Privacy of Others

Another element of good digital hygiene is to protect the identity of others. For example, never send group emails using To: or CC: (carbon copy) for each email address. You will reveal the email addresses for everyone on your list. This is especially problematic if you or another person saves the email message and displays it on the web, such as in a mailing list archive. This makes it easy for spammers and hackers to access and download all of those email addresses.

Use BCC: (blind carbon copy), to hide the email addresses from your recipients to protect everyone’s privacy. Use your own email address, and BCC the rest of the recipients, if your email software requires you to insert an email address into the To: box.

When using an email mailing list where you send messages to a single email address to a list of people, never CC: someone else in the same message. This will compromise the privacy of every CC’d recipient and the privacy of the list. Always check with the people on the list to ensure you are not taking unacceptable liberties.

If someone asks you to share an email address of a friend or colleague you should ask permission to share their email address, and state why the third party is requesting their email.

Be a Thoughtful Sceptic

So how can we protect ourselves if new threats are emerging all the time?

- Be conscious of where you put information that is “private” to you.

- Beware of the terms of service (ToS) of social media providers such as Facebook. Use a service such as Terms of Service: Didn’t Read (TOSDR) to help identify risky, overreaching services. You may be able to use certain privacy settings to protect your information.

- Always check the identity of a website before you enter any passwords or personal information. Secure certificates are generally trustworthy but be sure to check the names and details.

- Always ask whether you should trust a provider or a government agency. Always ask “who benefits when I do this?” What are their incentives?

- Protect your own data and be even more protective of others’ private information. For example, be cautious before posting information about yourself or someone else. Be especially cautious when posting pictures or videos of their children.

- Remember, complacency and unwarranted trust are your biggest enemies. A healthy paranoia is good for your digital health. Think about the great amount of time and effort it will take to regain your identity (and credit rating) if your information is compromised.

1.4.2 Activity: Analyzing Terms of Service (Didn’t Read)

1.4.3 Activity: Introduction To Reflective Journaling

1.4.4 Activity: Journal Entry on Digital Literacies

Summary

In this first unit, you have had the opportunity to learn about some of the impacts of “the digital“ on your life. You have started to build an academic knowledge management workflow, a pivotal skill essential for efficiently organizing, accessing, and leveraging information. Throughout the unit, you’ve actively engaged with digital tools, shared insights into your personal interactions with digital technology, and begun applying these tools to enhance your academic learning experience. Furthermore, you’ve developed a personalized understanding of digital literacy and explored how to protect yourself and others in digital and online contexts. As you progress through the course, take a moment to identify the specific literacies you aspire to refine and articulate the concrete steps you intend to take in pursuit of these goals.